Invasive alien plants, overgrazing, too frequent fires: there are many reasons why renosterveld can become degraded. Given that only 5% of renosterveld remains of its original extent, it’s vital to restore this Critically Endangered habitat when it becomes degraded.

In the midst of the United Nations Decade for Ecosystem Restoration (from 2021 – 2030), restoration has been highlighted as an important solution for nature around the world. It’s certainly also very relevant for renosterveld in the Overberg.

While the UN’s first rule of restoration is to do no harm, and therefore to leave habitats in as pristine condition as possible, sometimes it’s already too late for that. This is when active restoration becomes imperative.

A suite of recovery activities

In our Overberg renosterveld landscapes, the ORCT has adopted a number of restoration activities, funded primarily by WWF South Africa.

In the last year alone, our restoration efforts focused on invasive alien clearing and erosion control. Our contracting team, led by Willie Engel, cleared 595 ha of invasive alien vegetation, including 10 ha of initial clearing in an intensive and challenging setting.

And this has been the focus since the ORCT was established 11 years ago – with 2 080 ha cleared of invasive plants since that time.

Protecting renosterveld from livestock

But while invasive alien plants are a threat for many vegetation types, there are even greater threats to renosterveld – especially overgrazing by livestock. That’s why fencing has been erected on three properties in the last year to manage livestock grazing. In the past 11 years, more than 1 300 ha of remnant renosterveld has been managed for livestock through fencing.

At the same time, we’re working with one farmer to reintroduce Bontebok, in an area that would historically have provided a home to this species. The introduction of wild animals needs to be carefully managed, to ensure not only that the renosterveld isn’t negatively impacted, but also to make sure the game has sufficient food.

There’s a fine balance to restore renosterveld through fire. The habitat mustn’t burn too often, but evidence suggests that fire can be a tool to spark restoration. So we burn patches of renosterveld where appropriate (usually landscapes that haven’t burnt for between 12 and 20, or more, years). Since 2012, ecological burns led by the ORCT have been undertaken on 567 ha of renosterveld.

Experimenting with blankets, sausages and seeds

Aside from ploughing renosterveld (following which renosterveld cannot be restored in its entirety), erosion results in some of the most degraded habitats. This often happens following decades of poor land management – either on the veld itself, or on the surrounding transformed lands (croplands). And there are no hard and fast rules as to how to restore this level of degradation.

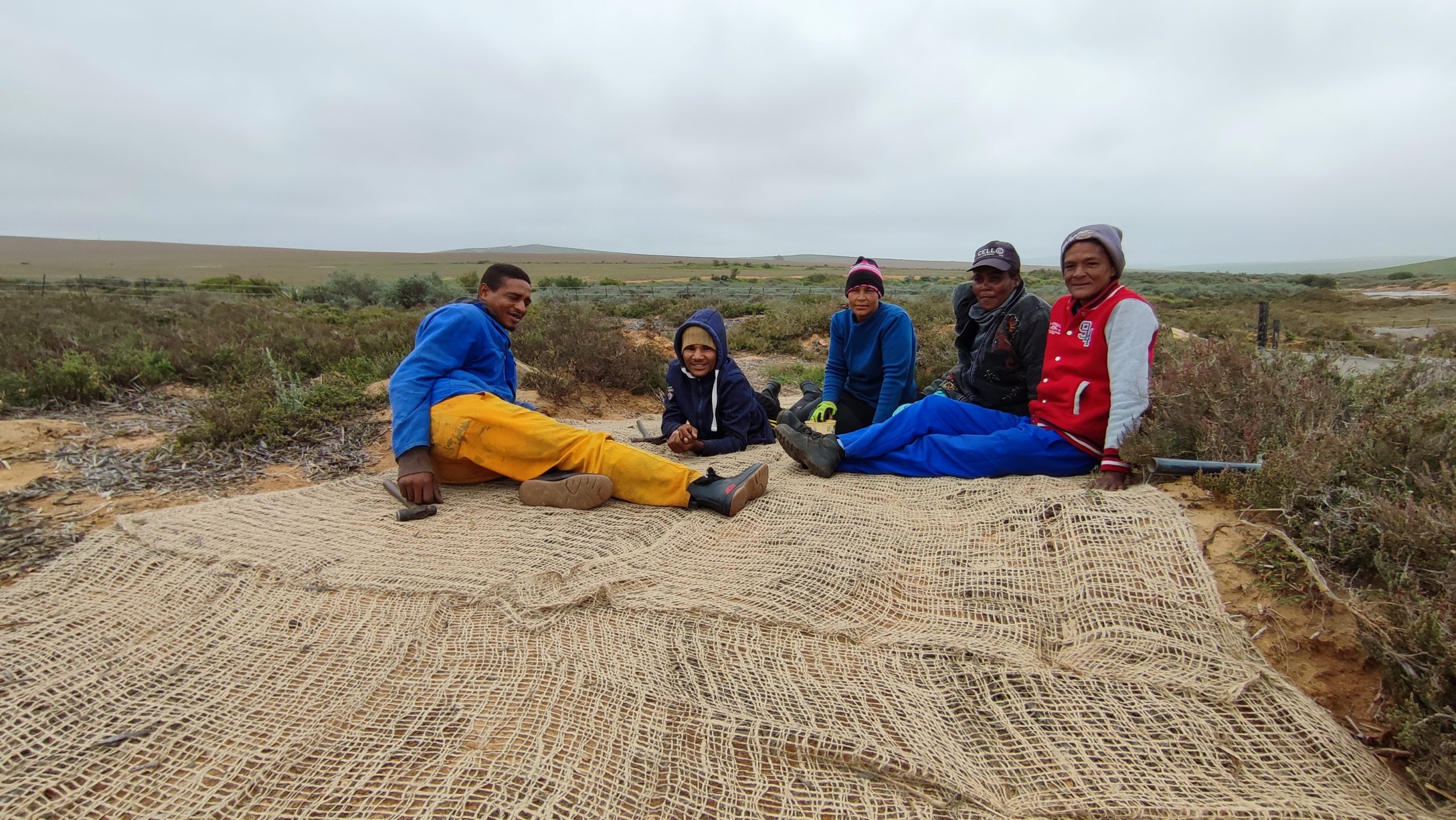

That’s why the ORCT is testing experimental restoration activities on eight hectares of eroded habitat in watercourses. Working with Willie and his team, we placed soil blankets, old fencing poles and blue gum poles to stabilise slopes. Erosion sausages were fixed to steep banks to slow the waterflow and facilitate the buildup of sediment. This in turn created favourable areas for seed establishment. We also seeded some sites with a few local species to test whether using this expensive method to kick-start the restoration process is in fact viable.

At one conservation easement on the banks of the Ouka River, we experimented with sowing a pioneer seedling mix of grasses and shrubs indigenous to the area. These were placed in hollows and on flat areas covered by biodegradable soil blankets enclosing mulch and straw, to keep the soil cool and moist. Succulent cuttings from the watercourse were also planted out. In the coming years, a suite of additional and more novel restoration methods will be adopted to test in renosterveld.

Even with these activities, while interventions like this will catalyse the recovery process, full recovery to its new or preferred state could take years, or even decades to centuries. In these instances, human support is needed even as the ecosystem recovers. Despite this, no fragment is too insignificant to restore, given the important role even these small fragments play as corridors or stepping stones for the movement of renosterveld-dependent wildlife.

Our sincere thanks to WWF South Africa for supporting the ORCT’s restoration work – at a time when renosterveld truly needs our help.