Could these be renosterveld’s cutest residents? Mice and shrews live in our Overberg renosterveld landscapes.

OVERBERG RENOSTERVELD TRUST

OVERBERG RENOSTERVELD CONSERVATION TRUST NEWS

Newsletter 35 | December 2024

by Dr Odette Curtis-Scott

Without renosterveld’s riches, our lives are poorer

A journalist for a well-known environmental programme once asked me,

“Why does it matter if renosterveld goes extinct?”

That was quite a moment for me. If he’d seen my face (it was a telephonic interview), he might have seen the shock. But I’m sure he felt it over the phone. It occurred to me: If I need to convince an environmental journalist that this habitat must be protected, how much more then those who don’t understand the role that nature plays?

So when well-known winemaker Bruce Jack asked me to contribute to his Jack Journal – just in time for World Wildlife Conservation Day celebrated today – it was a chance to really address this question. And to try and answer it in a way that would hopefully encourage even our cynical journalist that we need to do more for renosterveld.

Haarwegskloof: More than a place; it’s a feeling

The diary of Heidi Lücke-Haube.

What we do

ORT © 2012 – 2024 | Trust no IT851/2012 • PBO no 930039578 • NPO no 124-296

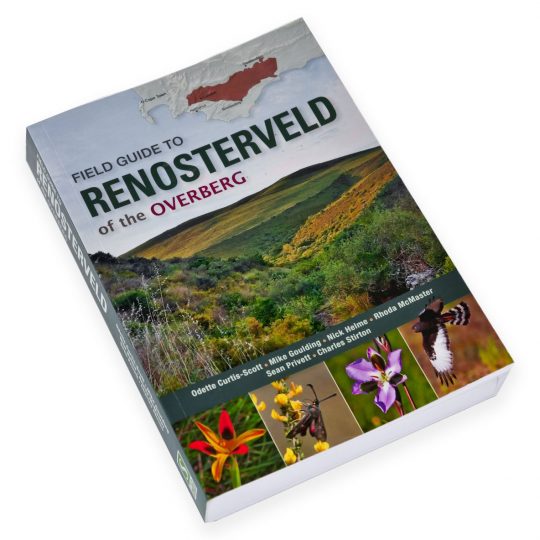

The Overberg Renosterveld Conservation Trust (ORCT) has launched the world’s first renosterveld mobile phone app, called Field Guide to Renosterveld. This allows you to identify 1 600 plant and animal species during your renosterveld adventures, all in the palm of your hand.

The app is based on the printed Field Guide to Renosterveld of the Overberg, released in 2020. The book contained over 1 100 species, of which just 14% were animals. The app builds on this and now contains over 1 600 species, of which 30% are animals that feature over 350 invertebrate photographs.

According to lead author and CEO of the ORCT, Dr Odette Curtis-Scott, the launch of this new app couldn’t come at a more important time for renosterveld. “The Field Guide to Renosterveld of the Overberg aimed to make threatened renosterveld more accessible to people. It is our hope that the app will add substantially to our heartfelt endeavors to make renosterveld even more accessible and loveable to everyone.

You don’t need to travel far to discover a whole world of treasures that live in the small fragments of renosterveld you’ll find spread across the Overberg.”

The experts behind the app

Co-authors to the app include ecologists who know and love renosterveld: The ORCT’s Conservation Manager, Grant Forbes as well as co-authors from the book version, Prof Charles Stirton and Rhoda McMaster. The app was created by designer mydigitalearth.com, who also created the apps for Sasol eBirds Southern Africa, Insects of South Africa, Sibley Birds (American field guide) and several other nature field guides.

The printed field guide took five years to complete and is based on 15 years of work in renosterveld. Work on the app, which includes 12 taxonomic groups, has taken another two years. According to Odette, “This shows the incredible amount of knowledge that app users can now easily access on their phones.”

Your list:

You can also use the app to log your observations of any of the species listed on the app. Here you can include where and when you saw the species, to start collecting data on your own renosterveld explorations.

Co-author Grant Forbes says the app is ideal for those on the move. “Hikers, nature lovers and citizen scientists can really make use of this tool, given that they are likely to take their phones with them during their adventures. The amount of information included on each species really brings renosterveld to life – and also shows just how threatened many of these species are.”

He adds that the app is also a powerful tool to showcase the diversity of renosterveld to land users. “It’s also for the custodians of the remaining renosterveld – landowners and land users, to really connect with and enjoy the gems that depend on the remaining renosterveld islands.”

The Field Guide to Renosterveld app features:

- An introduction to renosterveld

- A detailed description of the ecology of renosterveld

- Plant descriptions, divided into Ferns, Dicots, Monocots and Mosses & Liverworts

- Amphibians, fish and reptiles of renosterveld

- Over 100 insect and 35 arachnid families described, featuring photographs of over 340 species

- Photographs of 70 of the bird species you’ll find in renosterveld and surrounding farmlands

- And 37 mammals of renosterveld

BUY AND DOWNLOAD YOUR APP: here’s how:

The app is available on the Google Play Store and Apple App Store – and is called Field Guide to Renosterveld by mydigitalearth.com.

It’s available for just R249.99, and any future updates and improvements will be automatically updated on your version too.

What do pollinators turn to in the chilly winter months? In renosterveld especially, finding food can prove challenging when there are so few plants that are flowering.

Some of this food for pollinators comes from an unlikely source – from members of the Crassulaceae family. The Stonecrop or Plakkie family, as they are also known, are a family of herbaceous plants with succulent leaves. Because these thick, fleshy leaves are able to store water, and their tough skins help reduce evaporation, they are particularly well adapted to dry conditions.

But while many plants enter a period of dormancy during the winter, certain members of the Crassulaceae family take advantage of the cooler, wetter conditions to flower. These species add vibrant colour to an otherwise muted winter renosterveld landscape – as well as much-needed food for renosterveld critters.

Above: Rock Stonecrop (Crassula orbicularis). Photo by Grant Forbes

Taking advantage of the cooler climes

The Crassula genus – a prominent member of the Crassulaceae family – is especially important to hungry pollinators come winter. It comprises approximately 200 species, with plants that vary widely in form, from small ground-hugging species to larger shrubs. They are known for their patterned leaves and, in many cases, their striking flowers.

So on your next renosterveld hike in these cooler climes, look out for the likes of the Shy Flower (Crassula capensis), Watergras (Crassula natans) and the Sosatiebos (Crassula rupestris) – and see how they provide a meal to passing pollinators.

Above: Cape Stonecrop (Crassula capensis). Photo by Grant Forbes

Crassula capensis – Flowers May to November

This small, bulbous plant will already be showing off its white, star-shaped flowers on stems up to 10 cm long. The petals vary in number, but there are usually between 6-8 petals that are pinkish in colour on the underside.

You’ll find them on damp slopes from Clanwilliam to Riversdale. In the Overberg, they are most likely to occur on south-facing slopes.

Above: Crassula natans. Photo by Grant Forbes

Crassula natans – Flowers May to October

These are floating annual aquatic plants with stems of between 2 – 25 cm. The pretty flowers are cup-shaped, with four petals up to 2mm long, which are white to pinkish in colour.

Watergras occurs in moist depressions or pools, and is widespread throughout southern Africa.

Above: Crassula nemorosa. Photo by Grant Forbes

Crassula nemorosa – Flowers June to August

These pretty plants are most easily identified by their heart-shaped leaves with their smooth margins. Their flowers are cup-shaped but tiny – only between 2 – 3.5 mm in size, with silvery pink petals.

Crasssula nemorosa grows in rock crevices or on rocky slopes from southern Namibia to the Karoo and the Eastern Cape.

Above: Crassula cf. orbicularis. Photo by Grant Forbes

Crassula cf. orbicularis – Flowers June to November

The flowers of this species often grow in spike-like clusters. They’re tubular in shape, and white to yellow, tinged pink to brown in colour. Their leaves are opposite, oblong to elliptic in shape, creating some of those notable patterns associated with the Crassula genus.

This species occurs on rocky, sheltered slopes from Montagu and Potberg to KwaZulu-Natal. Interestingly, miniature plants that appear very similar to this species have been found in Rûens Silcrete Renosterveld along the lower Breede River.

Above: Crassula rupestris. Photo by Grant Forbes

Crassula rupestris – Flowers June to October

The Concertina Plant or Sosatiebos lives up to its name, with tightly packed, opposite and thickened leaves, resembling a ‘sosatie’. The flowers are white to pink, in round clusters on the ends of the stems.

They occur on dry, stony slopes, from Namaqualand to the Eastern Cape.

The need to protect Crassulas

Many Crassula species only occur in South Africa and nowhere else on Earth. That means that they need to be protected against the many threats they face. These include habitat destruction, climate change and over-collection for the horticultural trade. Conservation efforts such as the Overberg Renosterveld Conservation Trust’s conservation easement programme are therefore essential to protect these unique species and the ecosystems they support.

Find out more about Crassulas and other renosterveld species

The Field Guide to Renosterveld of the Overberg is packed with information regarding the Crassulaceae family, and thousands of other species that you’ll find in renosterveld – from flowers to animals. It’s the ideal way to come to know, and to come to enjoy, everything that renosterveld has to offer.

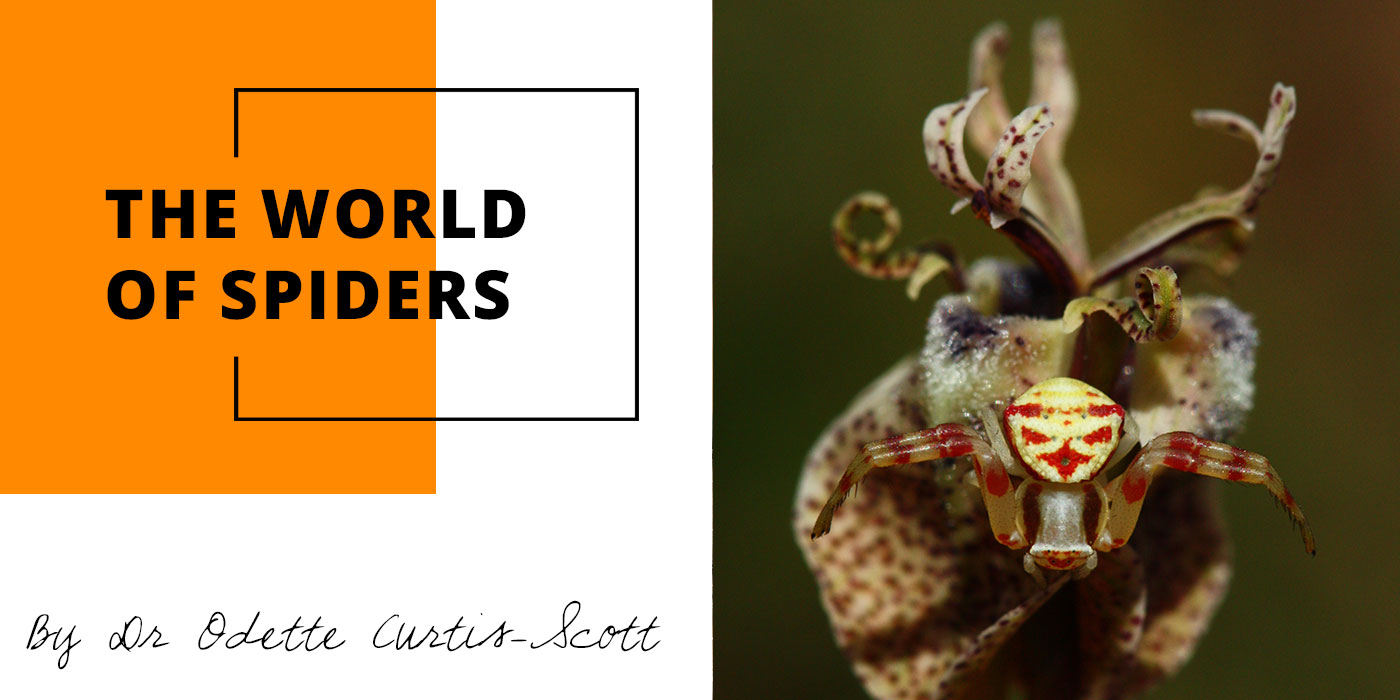

Above: Crab Spider on a Moraea inconspicua

Some plant-dwelling spiders are only 3mm in size, and are considered the ‘cuties’ of the spider world. Take a close look at their very endearing eyes, which make them particularly gorgeous subjects for macro-photography.

Above: Crab Spider with fly prey

Other plant dwellers include the Rain Spiders, the large spiders that often creep into your house before it rains. Despite their size, don’t be frightened of this species: they are shy, and would much rather run away than hurt you. Join me in getting to know some of the plant-dwelling spiders of Renosterveld.

PLANT DWELLERS

Oxyopidae: Lynx Spiders

This is a small genus with a global distribution. They do not make use of webs or retreats, although some species will hang from a dragline attached to the underside of a leaf. These beautiful spiders received their common name because of the way they hunt: they often catch prey with their legs by jumping into the air and catching insects in full flight.

Some genera are limited to living on a single plant species, others may have adaptations, such as long hairs (setae) on their legs, to enable them to blend in with the spikey grasses on which they hide in wait of passing prey. The female does not carry her egg sac around, but instead fastens it to a twig or leaf, where she guards and defends it.

Above: Lynx Spider, Oxyopes sp.

Salticidae: Jumping Spiders

Some of my favourites, the ‘cuties’ of the spider world, are the Jumping Spiders, belonging to the family Salticidae (hence known affectionately as ‘Saltis’ by spider fans), the largest family of spiders in the world, with over 350 species (and counting!) known from South Africa. They vary in size from 3 to 17mm and are active hunters. Some have particularly noticeable bristles in the eye region, giving the impression that they have long ‘eye-lashes’, thus making them extremely endearing. They often move fast and can be difficult to photograph but make beautiful subjects for macro-photography.

Above: Jumping Spider or ‘Salti’ Thyene inflata eating eggs, mostly likely belonging to an insect.

Above: Jumping Spider, Baryphas ahenus

Above: Jumping Spider, Rhene konradi

They do not make webs, but they do build nests in which to moult or lay eggs. They may even make use of such nests to mate or simply as a retreat during times of inactivity. The Jumping Spiders are in fact divided into three groups: hoppers, runners and intermediates. They are diurnal hunters with two noticeably large eyes (the other six are smaller) with complex retina which gives these incredible creatures unique resolution abilities found in no other animal of equivalent size. They detect and capture prey by means of stalking, chasing, leaping and lunging (or a combination of these methods).

Above: Jumping Spider Langelurillus namibicus, a very rare and poorly documented species in SA.

Above: Jumping Spider, Evarcha denticulata

Above: Jumping Spider, Dendryphantes sp.

Above: Jumping Spider, Heliophanus sp.

Above: Jumping Spider, Menemerus sp

Sparassidae: Huntsman & Rain Spiders

This is a family of free-living spiders, most of which are found on foliage, while a smaller proportion of them live on the ground. They do not make webs, but some make use of a silk-lined retreat or burrow in which to hide when not active. Most of the species in this group are active, nocturnal hunters. The ‘Rain Spiders’ Palystes spp. are the most encountered in houses, where they often appear a day or two before it rains (hence their common name); they come inside to hunt by making use of the lights which attract insects. They are one of our largest spiders and are well-known for the large, cocoon-like egg sacs which they construct amongst the vegetation.

These spiders tend to strike fear into people, mostly because of their size, but like all spiders, these are shy and do not want to bite. They will, however, raise their front legs in warning if they feel threatened and if taunted further, may bite (their bite is painful, but not medically significant). The smaller and very beautifully marked Arid Rain Spiders Parapalystes sp. are the most commonly-encountered in Renosterveld.

Top left: Typical rain spider nest. Top right and above: Palystes or Parapalystes sp.

Above: Palystes sp., gravid female

Thomisidae: Crab Spiders

This large and diverse family is made up of free-living spiders, most of whom are found on plants, with only a small number living on the ground. These attractive spiders come in a variety of patterns and colours (from bright colours such as pinks, green and yellows to white, dark brown or grey). They do not make webs or retreats but hide under vegetation or debris when not active.

Above: Crab Spider, Oxytate sp.

Crab Spider, left: Monaeses cf.pustulosus, right: Thomisus citrinellus with bee prey

They have evolved as expert ambushers and as a result have lost their agility and become sedentary, mostly moving with a sideways gait. This gait, combined with their two longer sets of front legs and their almost comical stance is responsible for them receiving their common name ‘Crab Spider’. The most frequently encountered genus in Renosterveld is Thomisus, the brightly coloured Crab Spiders which can change their colour to that of the flower from which they are ambushing prey, enabling them to surprise and capture unsuspecting flies and bees which visit the flowers.

Above: African Mask Crab Spider, possibly Synema sp.

Trochanteriidae: Scorpion Spiders

These spiders look a lot scarier than they are; they are free-living wanderers, found under bark or stones. They do not build webs or retreats. Very little is known about these unusual spiders whose flattened bodies are an adaptation to living in narrow crevices. As intimidating as they might appear, Scorpion Spiders are not medically significant.

Above: Scorpion Spider, Platyoides sp.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank you National Lotteries Commission of South Africa for their assistance with the purchase of additional camera equipment to support the ORCT’s photographic work. A big thank you to Astri Leroy for checking this piece for correctness and teaching me a lot! My sincerest thanks to the Spider Club of South Africa for their fantastic Facebook page, led by a group of passionate spider experts and members who are only too willing to give of their time to identify photographs and answer peoples’ questions. I highly recommend joining this club and / or following them on Facebook: www.spiderclub.co.za or Facebook: @theSpiderClubOfSouthernAfrica.

Visit the National Lotteries Commission (NLC) website to find out about other projects supported by the NLC.

This year we celebrate the launch of the UN Decade of Restoration. The main aim of this call to action is to prevent, halt and reverse the degradation of ecosystems around the world. As one of the world’s most biodiverse and yet threatened ecosystems, the Renosterveld of the Overberg deserves our focus around this.

South Africa is internationally mandated to conserve Critically Endangered ecosystems such as Overberg Renosterveld, that have suffered extensive habitat loss and have relatively little still surviving.

It is often said that ecological restoration is needed in areas where so much of a threatened vegetation type has been lost that national and international goals for conserving a certain percentage of a vegetation type are otherwise impossible to meet.

However, ecological restoration is challenging to undertake in Renosterveld vegetation, where small surviving patches of vegetation are now surrounded by high value productive agricultural lands.

Furthermore, once Renosterveld has been ploughed multiple times, changes in soil structure and loss of its original range of habitat niches mean that its former levels of habitat biodiversity have been lost forever.

Above: Moraea debilis

However, we can restore Renosterveld through management interventions that improve the habitat condition and conservation value of what vegetation still remains.

The Overberg Renosterveld Conservation Trust (ORCT) is doing just this through an innovative project funded by WWF South Africa.

This work builds on two different projects that have been previously undertaken by the ORCT, namely the WWF Nedbank Green Trust Watercourse Restoration and the Table Mountain Fund Conservation Easement Project.

A conservation easement is a conservation servitude which encompasses a whole property to ensure conservation in perpetuity of Renosterveld vegetation there. This agreement is written into the title deeds of the farm and runs with the land from one landowner to the next one.

Landowners on a property with a signed conservation easement can access additional support for conservation of the Renosterveld over which they are custodians. Support available can include assistance with fire management, control burns and post fire monitoring, alien clearing and regular monitoring of flora and faunal biodiversity.

This project, primarily funded by WWF South Africa has provided additional support in signing up additional Renosterveld under conservation easements and thus growing the percentage of Overberg Renosterveld that can be conserved in perpetuity.

Furthermore, it has provided additional funding for ongoing management needs of existing conservation easement sites. This ensures that landowners who have joined the programme continue to engage with conservation action and restoration activities on their land.

Those considering signing conservation easements have also been encouraged to join the programme by following in the footsteps of conservation success of those who have already done so.

Through this work being undertaken in Overberg Renosterveld, vital habitat is secured for conservation alongside implementation of key management interventions within the Overberg Wheatbelt Important Bird Area.

This helps to conserve and improve habitat for threatened birds such as the Black Harrier, Secretarybird and Southern Black Korhaan, as well as the many other endemic species found here, such as Cape Spurfowl, Greywinged Francolin, Agulhas Longbilled Lark, Agulhas Clapper Lark and others.

One of the key restoration interventions of the project has been to significantly reduce the footprint of and impact on Overberg Renosterveld of invasive alien Acacias such as Port Jackson (Acacia saligna). This has been achieved through mapping priority infestation sites and then implementing alien clearing work.

One of the main threats facing Overberg Renosterveld vegetation is overgrazing by domestic livestock. Overgrazing causes long term decreases in species richness and diversity in these ecosystems, and optimal grazing management is key to avoid further degradation of Renosterveld vegetation that may be irreversible.

One of the main solutions to this project has been through supporting passive restoration of overgrazed veld and reducing the likelihood of overgrazing taking place by providing financial support to farmers to put up fencing at key conservation easement sites to facilitate best practice livestock grazing management.

In some cases, such interventions are combined with implementing an ecological burn, which also restores old, degraded vegetation to its former glory, if undertaken correctly and protected from livestock post-burning.

Over the last three years, through the support of WWF South Africa we have been able to significantly expand the conservation footprint in Renosterveld in the Overberg, conserving more hectares of Renosterveld in perpetuity. We have also been able to support willing and passionate landowners in their efforts to conserve and manage their veld in reaching their conservation goals.

We would like to acknowledge the WWF-SA Table Mountain Fund and WWF South Africa for supporting the ORCT’s conservation easement project as well as the amazing farmers we are lucky enough to work with to conserve their Renosterveld. Please consider supporting the vital work of the Overberg Renosterveld Conservation Trust to help us manage and conserve more Renosterveld in perpetuity.

OVERBERG RENOSTERVELD CONSERVATION TRUST NEWS

Newsletter 23, Dec 2020

by Dr Odette Curtis-Scott.

A startling spring and summer; And check these Renosterveld gifting ideas…

This has been a spring and early summer season to remember. We’ve seen Renosterveld species flower that haven’t flowered for years during the drought. And we’ve seen a show more prolific than we ever could’ve imagined.

My colleagues, Grant and Petra, have shared their spring experiences in this newsletter. They bring Renosterveld to life in these colourful blogposts. And capture why I couldn’t receive any better Christmas present than seeing how our Renosterveld landscapes came alive over the past few months.

Of course, it’s not all good news. The transformation of Renosterveld for agricultural purposes remains one of the biggest threats. We’ve also seen evidence of over-grazing, and the incorrect use of herbicide.

As the ORCT, we can continue to respond to these threats.

– We work closely with farmers (as can be seen in the number of hectares we have signed into conservation easements to date) to support good Renosterveld management.

– We facilitate Renosterveld research.

– And we closely monitor the remaining Renosterveld parcels, including the wildlife living here.

To all our donors and friends, thank you! We couldn’t do this without your help. Here’s to a wonderful festive season to you and your families. We look forward to 2021 – and a big year for biodiversity!