OVERBERG RENOSTERVELD TRUST Home About Vision & Mission Our Role Our Team Sponsors & Partners Our Patrons & Ambassadors Annual Report 2024 Gallery What we do Renosterveld – the Story...

OVERBERG RENOSTERVELD TRUST

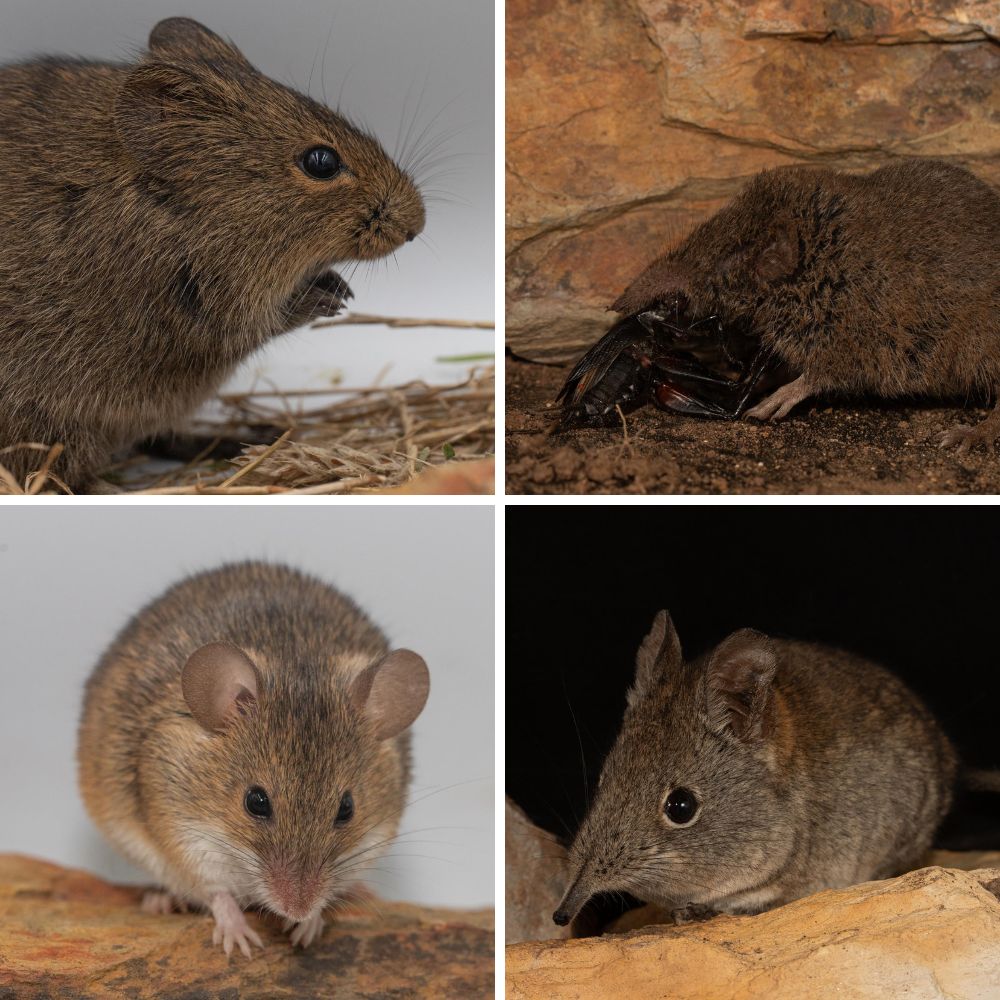

Could these be renosterveld’s cutest residents? Mice and shrews live in our Overberg renosterveld landscapes. And the Overberg Renosterveld Trust is on a mission to learn more about these critical critters.

But this is no easy task. Mice and shrews of renosterveld are quick to disappear when they see any movement. Many also only move around at night. That’s why we’ve teamed up with the expert: Dr Shaun Welman from the University of Cape Town.

Here’s what we know…

Monitoring over the years has brought to life the tiny mice that you could see here. These include:

– Cape Spiny Mouse

– Namaqua Rock Mouse

– Pygmy Mouse

– Southern Vlei Rat

– Four-striped Grass Mouse

– Grey Climbing Mouse

– Cape Rock Sengi

– Reddish-Grey Musk Shrew

– Lesser Dwarf Shrew

Small mammals are a vital component of the renosterveld ecosystem: they are important herbivores, foraging on vegetation and seeds (in the case of mice and rats), and predators of invertebrates (in the case of shrews and sengis), while they themselves are a critical food source for many predators (from small mammalian carnivores like mongooses and African Wild Cats to birds of prey). Some even perform a pollination function, foraging on the musky nectar of some ground Proteas, for example.

The Pygmy Mouse is one of the world’s smallest rodents – weighing ONLY 6g. Striped Mice are an important food source for many raptors in renosterveld, such as Black Harrier and Black-winged Kite, whose diets can be dominated by the species. The diversity adaptations to specific niches are remarkable: for example, the incredibly agile Grey Climbing Mouse has a semi-prehensile tail for climbing grasses and shrubs, and the endearing Sengi has large, rounded ears and an elongated probiscis (nose) for foraging small invertebrates, particularly ants and termites.

Together with Dr Welman and his post-graduate students, we hope to learn a lot more about small mammal populations in the renosterveld in the coming years.

And we’re also testing different methodologies for surveying small mammals.

This will allow us to see which could be the most effective monitoring tools over time.

- We’ve now invested in camera traps that have been fitted into small boxes that are baited to attract and photograph these mice and shrews. In order for the cameras to capture these tiny creatures more clearly, a lens from a pair of reading glasses is placed on the camera lens. This helps to capture the details on animals on the pictures so that they can be identified.

- At the same time, we are also putting out live-traps called Sherman traps which catch the small mammals, unharmed. These traps capture the animals by luring them in with bait like droëwors and peanut butter-oat balls. Once the individuals are weighed and marked with a small fur clipping (to measure re-captures), they are immediately released.

The goal is now to build a database of small mammal surveys – including population densities and diversity relative to veld age (i.e. time since last burn) and, as the research grows and develops, we will also look at diversity and population sizes in different veld types, through a series of postgraduate studies.

Our sincere thanks to Dr Welman and the UCT team for working with the ORT on this exciting project. And a huge thank you to the Fynbos Trust for supporting the purchase of the ORT’s Sherman traps to help with our monitoring work.

Images: Odette Curtis-Scott

Latest Renosterveld News

A weekend of fire and spice: Our first retreat at Haarwegskloof

The first Wild & Wise Retreat at Haarwegskloof Renosterveld Reserve unfolded under a soft winter sun during a June weekend.

A rare look into the nocturnal life of the aardwolf

Aardwolves have long been resident in the Overberg region, including at the Haarwegskloof Renosterveld Reserve. Recently, we were fortunate to gain some insight into their secretive behaviour.

What we do

ORT © 2012 – 2025 | Trust no IT851/2012 • PBO no 930039578 • NPO no 124-296

The flora of South Africa’s Greater Cape Floristic Region (GCFR) is known worldwide for its extraordinary botanical diversity, from the huge blooms of Proteas to the tiniest most delicate of bulbs. Many plants from the GCFR’s Overberg Renosterveld are known for their beautiful and spectacular flowers.

However, with such overwhelming diversity, some plant groups in the GCFR end up being overlooked by scientists, simply because of their relatively plain appearance. An example of this is the genus Thesium, whose taxonomy is the topic of a new paper published by Daniel Zhigila, Antony Verboom and Muthama Muasya from the University of Cape Town in the academic journal Taxon.

Above: Thesium dmmagium

Photos were contributed to the paper by Dr. Odette Curtis-Scott, Director of the Overberg Renosterveld Conservation Trust. These photos illustrated examples of Thesium found growing in Overberg Renosterveld vegetation found during biodiversity surveys in this Critically Endangered vegetation.

The genus Thesium was first described by Swedish botanist Linnaeus, who identified four different species when he described the genus in 1753. The genus Thesium has around 360 species worldwide, but the majority are found in southern Africa. There are around 86 Thesium species in the GCFR.

Above: Thesium frisea var thunbergii

The majority of Thesium are hemiparasitic shrubs, meaning that they live as parasites on other plants, but still derive some of their nutrients from photosynthesis. Some are suffrutices, which are woody perennial plants that have a woody base. There are also a few annual Thesium species too.

There are several Thesium species found in Overberg Renosterveld vegetation, with eleven different taxa described in the Field Guide to Renosterveld of the Overberg. One of these is Thesium stirtonii, which is named in honour of Professor Charles Stirton, special advisor to the Overberg Renosterveld Conservation Trust (ORCT).

Above: Thesium stirtonii

Findings presented in the 2020 paper by Daniel Zhigila and colleagues are based on his PhD research into the taxonomy of genus Thesium. This research has resulted in the publication of two key taxonomic research papers to date.

Some of the fieldwork that formed part of Daniel’s research was undertaken while staying at the Renosterveld Research and Visitors’ Centre at Haarwegskloof Renosterveld Reserve. The reserve is owned by WWF South Africa and run by the ORCT.

Above: Thesium microcarpum

This research used genetic sequencing data to analyse the phylogenetic relationships within the genus Thesium. This means that the data are used to examine the relationships between taxa, producing a tree that illustrates how species are related in an evolutionary context.

Findings from this research identified the need for a new infrageneric classification of the genus Thesium. The dataset demonstrated that the four separate genera that Thesium had been previously split into should be sunk into the genus Thesium.

Above: Thesium nigroperianthum

Furthermore, the data also revealed five major clades within the Thesium genus. Clades are taxa that group collectively on a phylogenetic tree, indicating that they have evolved from one common ancestor. The Zhigila et al. paper splits these clades into five newly recognised subgenera.

Above: Thesium funale

So why is this research important? Taxonomic research such as this helps us to better understand relationships between plant species, and how these species are distributed geographically. This helps biodiversity professionals to better understand their conservation status, feeding into conservation planning.

Building on the seminal findings of his PhD, Daniel has been awarded a Smuts postdoctoral fellowship to continue his work at the University of Cape Town for a further 12 months, working alongside Professor Muthama Muasya (ORCT Trustee) and Dr. Ute Schmiedel.

Above: Thesium rhizomatum

This work will focus on answering questions around phylogenetic diversity patterns in quartz fields across South Africa, including in the Overberg, Klein Karoo and Namaqualand. We look forward to welcoming Daniel back to the Overberg soon.

Great strides have been made in increasing knowledge of the taxonomy, biodiversity and ecology of Overberg Renosterveld since the founding of the ORCT. Strong research partnerships between the ORCT and academic institutions continue to support effective applied research projects that help to inform our vital conservation work.

Above: Thesium spinosum

Supporting applied Renosterveld focused research undertaken through our well-equipped research centre at Haarwegskloof helps us to build knowledge to improve management practices in this Critically Endangered vegetation to best achieve conservation goals. Please consider making a donation to the Overberg Renosterveld Conservation Trust, allowing us to continue our vital work.

Bio of Daniel Zhigila

Dr Daniel Zhigila is a Nigerian, from sub-Saharan Africa. He was a Graduate Assistant with the Botany Department, Gombe State University, Nigeria, before enrolling for his PhD in the University of Cape Town. For his PhD research he has made significant progress in helping to unravel the complexity of a very difficult priority research genus, Thesium L. (Sanatalaceae). As part of this research he has described eight species new to science and made tremendous nomenclatural changes in the genus.

Further Reading

Curtis-Scott, O.E. Goulding, M. Helme, N. McMaster, R. Privett, S. Stirton, C. (2020) Field Guide to Renosterveld of the Overberg, Struik Nature, Cape Town, South Africa.

Zhigila, D.A. Verboom, G.A. Muasya, A.M. (2020) ‘An infrageneric classification of Thesium (Santalaceae) based on molecular phylogenetic data’, Taxon (Volume 00): pp. 1-24.

Above: Thesium nigroperianthum

One of the jewels in the crown of Overberg Renosterveld is Haarwegskloof Renosterveld Reserve, home to the largest continuous fragment of Renosterveld vegetation on Earth. The reserve is also home to the world’s first research and visitors’ centre dedicated to renosterveld, run by the Overberg Renosterveld Conservation Trust (ORCT).

Our postgraduate research group use the research centre as a home away from home for their work, producing valuable research outputs that inform conservation of this critically endangered vegetation.

Above: Polhillia curtisiae taken at Haarwegskloof. Photo: Zoë Chapman Poulsen.

Botanist and specialist legume taxonomist Brian Du Preez has collaborated with colleagues Leanne Dreyer, Charles Stirton and Muthama Muasya in publishing a new revision for the genus Polhillia, representing one of the main outputs of his Masters research. This revision identifies and describes four new species in the genus, namely P. groenwaldii, P. stirtoniana, P. xairuensis and P. fortunata.

Polhillia groenwaldii is named to honour ecologist, conservationist and former employee of the ORCT Jannie Groenewald for his extraordinary work in increasing our knowledge of new species as well as new populations of threatened species across the Overberg region. Jannie was also responsible for ‘finding’ this undescribed species in the Bonnievale region.

Above: Polhillia stirtoniana

Polhillia stirtoniana is named to honour botanist and legume expert Professor Charles Stirton, who was instrumental in the founding of the ORCT.

P. xairuensis is derived from the Hessequa Khoi name for the Suurbrak area (where it was first found), !Xairu which means ‘beauty’ or a ‘place called Paradise’.

Not only were ‘new’ species described in this paper, but the ‘known’ species were also revised, most notably (for the Overberg): What had previously been known as P. canescens was examined against the first and only collection of P. connata and it was decided that these were in fact the same species, this P. canescens is now re-named P. connata. Also, what we had previously considered to be the least-threatened P. pallens, was in fact two species: with the population along the Breede River retaining the name P. pallens and the population around Haarwegskloof and Plaatjieskraal becoming the ‘newly described’ P. stirtoniana.

Members of the genus Polhillia are well represented in Overberg Renosterveld, with six of the twelve species being present there – all of them in the Eastern Rûens. The Polhillia genus forms part of the Fabaceae or pea family. It is the third most threatened plant genus in South Africa.

Given the high threat status of all members of the genus Polhillia, it was considered a high priority for taxonomic revision so that we could better understand what species were within the genus and how they could be identified. Proper identification of species is crucial for conservation. Naming species is one of the first steps in conserving them effectively.

Above: P. brevicalyx pod

The Red List status (or the revision thereof) for the species is also proposed in the paper as follows (Overberg species only): P. curtisiae (EN (previously CR, but additional populations have now been found)), P. xairuensis (EN), P. connata (VU), P. pallens (VU), P. brevicalyx (CR), P. stirtoniana (NT).

This vital taxonomic research involved many hours in the field and the herbarium. Herbarium specimens offer a baseline of understanding of where we have already recorded a species. They also offer clues about the habitat preferences of a species, of where else we might find them growing.

Botanists can then take this information to the field, where the treasure hunt begins. Most Renosterveld is on private land and is therefore relatively underexplored. With several Polhillia species previously only known from one locality, the hunt was on to find and identify other subpopulations. This work then supports conservation planning and action by building a more detailed picture of the distribution of species in the genus.

This seminal work demonstrates how effective partnerships between academic researchers and conservation professionals can drive effective applied research, producing outputs that feed into conservation planning and action. We look forward to welcoming more researchers to the centre at Haarwegskloof, building our knowledge of this fascinating ecosystem.

Above: Polhillia connata

Strong research partnerships help us use the most up to the minute findings to inform our vital conservation work. Please consider making a donation to support the Overberg Renosterveld Trust and the Haarwegskloof Renosterveld Reserve.

Further Reading

Du Preez, B. (2019) Polhillia on the Brink: Taxonomy, ecophysiology and conservation assessment of a highly threatened Cape legume genus, Unpublished Masters thesis, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa.

Du Preez, B. Dreyer, L.L. Stirton, C.H. Muasya, A.M. (2021) ‘A monograph of the genus Polhillia (Genistaceae: Fabaceae)’, South African Journal of Botany (Volume 138): pp. 156-183.

Viewed with terror and often persecuted, scorpions are some of southern Africa’s most feared and misunderstood creatures. South Africa is home to a rich scorpion fauna, and if one takes the time to learn a little more, they are in fact truly fascinating. This week we will take a closer look at the scorpions found in the Renosterveld of the Overberg and how we can best peacefully live alongside these extraordinary and curious creatures.

Scorpions are found on six of seven continents on earth, with 2 352 different species currently known worldwide. They can be found living in environments from tropical rainforest, to grasslands and snowy mountain tops at more than 5 500m asl. More than 135 scorpion species are found in southern Africa.

Above: Parabuthus capensis

Scorpions are highly secretive creatures, becoming active mostly at night. However, the average scorpion spends more than 92% of its life without moving due to their incredibly slow metabolisms. This means that some scorpion species are able to survive without food for more than a year at a time.

With the earliest known scorpion fossils dating back more than 425 million years, scorpions have been identified as one of the earliest form of land animal. This makes them even older than the first dinosaurs to roam the earth. Some of the earliest scorpions inhabited lagoons and estuaries and were primarily aquatic. Many early scorpion species were far larger than those seen today, growing up to a metre in length.

Scorpions are perhaps best known for being venomous, an adaptation used in hunting their prey and defending themselves against larger predators such as honey badgers. Thick tailed scorpions are able to hunt and subdue prey considerably larger than themselves. Those with larger and thicker pincers and a thin tail are weakly venomous. Those with a thick tail and thin pincers are highly venomous with their neurotoxic venom being medicinally significant.

There are four different scorpion species that are most likely to be encountered in Overberg Renosterveld.

Thick Tailed Scorpion/Dikstertskerpioen (Parabuthus capensis)

Easily identified by its thick tail, small pincers and orange-brown colour, the Thick Tailed Scorpion is the most venomous scorpion species found in Overberg Renosterveld. It sometimes hides underneath rocks and logs but constructs burrows mostly in open ground. The sting can be fatal (in rare cases) for young children and elderly people and emergency medical attention should be sought immediately following a sting.

Bark Scorpion/Boombassskerpioen (Uroplectes lineatus)

These small scorpions are most commonly found living underneath rocks or in lose bark. They are sometimes encountered in houses and are responsible for most scorpion stings in the region. The sting is painful but not deadly.

Burrowing Scorpion/Graafskerpioen (Opistophthalmus latimanus)

Like their name suggests, this scorpion species constructs burrows underneath rocks and logs. They use these burrows in order to ambush their prey. They can deliver a painful sting, but are not deadly.

Black Scorpion/Swartskerpioen (Opisthacanthus capensis)

This scorpion is easily identified by its large pincers and black colouration. It is relatively non-aggressive in comparison with other scorpion species. It is consumed as food by bat-eared foxes and some mongoose species.

Scorpions found in this part of the country are rarely known to enter houses. If they are known to occur in the area then it is advisable to shake out boots and shoes left outside at night. Firewood should also be handled with care as scorpions, particularly bark scorpions, can sometimes use a wood pile for shelter. If walking at night then closed shoes or boots should be worn.

Scorpions can be observed at night and all species will glow under a UV light. The only exception is when a scorpion has just moulted. This phenomena can last for millions of years and can also sometimes be seen in fossilised scorpion specimens. Scorpions should not be taken from the wild. It is illegal to collect and keep them and few South African species will survive long due to their specialist habitat needs.

We still know relatively little about scorpions in southern Africa, and particularly in Overberg Renosterveld. However, we do know that habitat transformation such as that threatening these Critically Endangered ecosystems is one of the main threats facing scorpions and the creatures further up the food chain that depend on them for food. It is therefore important for the ORCT to continue its vital work in conserving Overberg Renosterveld ecosystems and all the wildlife large and small that calls them home.

If you would like to consider supporting the work of the Overberg Renosterveld Conservation Trust in conserving these biodiversity and critically endangered ecosystems, more information can be found here.

If you are interested in getting your scorpion observations (photographs) identified, consider joining the Facebook Group ‘Scorpions of Africa’.

Read more about the Poison Information Helpline here.

Further Reading

Curtis-Scott, O.E. Goulding, M. Helme, N. McMaster, R. Privett, S. Stirton, C. (2020) Field Guide to Renosterveld of the Overberg, Struik Nature, Cape Town, South Africa.

Leeming, J. (2019) Scorpions of Southern Africa, Struik Nature, Cape Town, South Africa.

We’re encouraged to smile every day. But especially so on World Smile Day (2 October).

For some Renosterveld animals, though, ‘smiling’ comes naturally. And their happy countenance is likely to bring a smile to your face – simply because they’re so cute (or in some instances, just a little bit ugly).

Here are our 5 favourite smiling animals that live in our Overberg Renosterveld landscapes, as featured in the Field Guide to Renosterveld of the Overberg.

Above: Cape Fox (Vulpes chama) 📸 Cliff & Suretha Dorse

Cape Fox

This little smiling mammal is the only true fox in South Africa. It’s small, swift and agile, and uses its bushy tail to deceive pursuers. They make their own dens for shelter under the ground, or also hide in thickets or dense bushes, and sometimes hollow termite mounds. They’re harmless to livestock, and feed mostly on small rodents.

Above: Scrub Hare (Lepus saxatilis) 📸 Cliff & Suretha Dorse

Scrub Hare

You’ll generally see this smiling hare in the evening or at night. During the day, they sneak away to hide under grass or bushes, or create a little indent in the ground to lie flat, where they are well camouflaged. They’re also quite picky eaters, preferring green grass to other vegetation types.

Above: Bat-eared Fox (Otocyon megalotis) 📸 Brian Taylor

Bat-eared Fox

The Bat-eared Fox’s smile is very noticeable; surpassed perhaps only by their extremely prominent ears. The ears are full of blood, and help to keep the animal cool, especially during our warm Overberg summers. They are real family mammals: they live in groups in their burrows, and are wonderfully brave parents to their young.

Above: Cape Serotine Bat (Neoromicia capensis) 📸 Field Guide to Renosterveld of the Overberg

Cape Serotine Bat

This smile may be upside down. But it can’t be left out in terms of the cuteness factor. The Cape Serotine Bat is very small – only about 8-9cms. The bat finds a favourite route, and then usually sticks to the same route when it emerges in the evening to hunt for insects. While the upside-down smile may make it look a little grouchy, it’s harmless to people.

Above: Southern Rock Agama (Agama atra) 📸 Field Guide to Renosterveld of the Overberg

Southern Rock Agama

This is the only smile on our Renosterveld list that can actually change colour. The Southern Rock Agama male usually has a bright blue head (he uses the colour to communicate with other individuals). But these large lizards can change colour to merge into the surroundings when they have to.

These and 135 other smiling (and non-smiling) animals are featured in our new book, the Field Guide to Renosterveld of the Overberg. The guide aims to bring the overlooked Renosterveld ecosystems of the Overberg to life. It includes nearly 1000 Renosterveld species, and those animals that survive and live in the habitat.

Resources

The Renosterveld of South Africa’s Overberg region is one of the world’s most biodiverse Mediterranean type shrublands. It is also one of the world’s most threatened ecosystems. With just 5% of its former extent remaining, the Overberg Renosterveld that is left falls far short in terms of spatial area for government recommendations for conservation. This means that all Renosterveld that survives today is vital for conservation, every plant and every animal. With most surviving Overberg Renosterveld on private land, those landowners become one of the most important custodians of this highly imperilled ecosystem.

Above: Haworthia minima

South Africa’s biodiversity, and particularly lowland ecosystems such as Renosterveld, are under siege from all sides, facing a variety of different threats, from clearance for agriculture to alien invasive plants. One lesser known threat facing South Africa’s flora is poaching, something normally associated with the illegal killing of animals such as rhinos and elephants. South Africa’s plants are the lesser known victims of poaching, which is defined as the illegal collection and removal from the wild of plants or parts of plants such as seeds or bulbs. This activity particularly impacts upon threatened species, as well as compromising the integrity of ecosystems, pollination networks and ecological niches for habitat specialists.

Plant poaching may be for medicinal use, the horticultural trade or any other purpose for which plant material is removed from the wild. It is illegal in South Africa to remove any indigenous plant material from the wild, transport it between provinces, or export it from South Africa without the necessary government permits. If you have a bona fide reason for collection of plant material, for example research or conservation, the necessary permits can be obtained from your nearest CapeNature office (or call 087 087 4088).

Above: Gibbaeum haartmanianum

What few people realise is that plant poaching also includes collection of plants or propagation material from the veld for growing in private gardens. It is illegal to dig up plants for your own garden from the veld or side of the road. It is important to rather purchase your plants through reputable nurseries, who sell cultivated stock while holding the appropriate permits, rather than plants that have been harvested illegally from the wild. South Africa has a large network of specialist growers so even the most discerning plant enthusiasts should be able to source what they would like to grow. In short, wild plants should stay where they belong in the veld.

South Africa’s world class and close-knit community of biodiversity professionals are well aware of the plant poaching problem, and work closely with law enforcement to catch and prosecute any offenders. The community cares deeply about South Africa’s biodiversity heritage remaining intact and where it belongs in the veld. Conservationists and environmental law enforcement are thorough and vigilant, and the consequences of being caught poaching plants is severe, with high fines and jail time on the cards for those caught.

So what can we do to help the conservation community combat the plant poaching problem? Firstly, if you are a landowner and custodian of Renosterveld or any other natural veld on your land, always pay attention to who has access to your veld and that visitors requesting permission for access are who they say they are. If you catch anyone suspected of poaching in your or anyone else’s veld, always report it to your local conservation authority such as CapeNature. Get to know your own Renosterveld by walking in it regularly so that you can pick up on any changes or species disappearing through illegal collection if poachers are trespassing and stealing plants from your land.

Above: Haworthiopsis venosa

Secondly, if you are enthusiast who photographs plants in the veld, particularly rare or threatened species that are more vulnerable to collection, always ensure that photographs online in the public domain do not give away locality data that may help plant poachers in their illegal collecting. If you are posting on biodiversity sharing sites such as iNaturalist then species sensitive to illegal collection always have their localities automatically hidden. However, if you are in doubt and not sure of the species ID, always hide the locality until your photo has been assigned a formal ID.

It is also important to make sure that photos cannot be used to identify specific localities by showing distinctive landmarks or are not using captions giving away which farm/GPS the plant can be found. Ensure that GPS metadata cannot be harvested from your photos online giving away the locality that the photo was taken. Also if you are contacted requesting locality details for specific species, do not give them away unless you are sure that person is a known bona fide biodiversity professional or conservation volunteer working with a reputable organisation.

Plant poaching is a significant problem facing South Africa’s unique biodiversity and natural heritage, but if landowners, biodiversity professionals, citizen science volunteers and law enforcement agencies work together, illegal poachers pillaging the country’s imperilled species can be discouraged, caught and prosecuted for their actions. We are watching and we care, so that our imperilled species can stay where they belong in the veld.

Above: Babiana patula

Winter is a time for wild weather in the Cape, where intense cold fronts roll in off the Atlantic bringing cold weather, heavy rainfall and snow in the mountains. It is a time when many of us batten down the hatches and stay cosy at home. For the Renosterveld, winter is the time that much needed rain comes to the veld, when plants start to grow ahead of blooming during the spring season.

This biodiverse Mediterranean type shrubland is known for its extraordinary diversity of geophytes or bulbs, most of which bloom during spring. But the beautiful Babianas are ahead of the game, often coming into bloom in the Overberg fleetingly during the coldest late winter months, leaving behind just their distinctive corrugated sword-shaped leaves as many botanists emerge later to start their spring biodiversity surveys.

The genus Babiana forms part of the Iridaceae family, comprising a total of 80 known species. The majority of Babiana species are found in South Africa’s winter rainfall zone, with the centre of diversity for the genus being in Namaqualand and the Richtersveld. Members of the genus are easily recognised by their pleated leaves and very deep seated corms that sit relatively deep in the ground, often in underground cracks in the rocks to avoid predation by mammals such as baboons and porcupines. There are a few species that grow on sandy soils, but the majority are found on clay soils derived from shales.

Babiana foliosa

Last seen in 1951 in the Riviersonderend area, Babiana foliosa is feared to be possibly extinct. It is only known from a single collection growing on loamy flats in Central Rûens Shale Renosterveld. Since this specimen was first collected, much of the habitat in the area has been lost as a result of transformation for agriculture.

Above: Babiana montana

Babiana montana

Despite it’s rather misleading species epithet name, Babiana montana is found in both lowland and mountain habitats. It is described in older publications as only occurring on limestone and sandstone slopes, but also occurs in Western and Central Rûens Shale Renosterveld with a distribution between Caledon and Bredasdorp. Babiana montana is currently known from only three localities, but it is possible there are more to be found through biodiversity surveys. Surviving plants are threatened by habitat degradation through overgrazing and alien plant invasion and habitat loss through transformation for agriculture. It is therefore listed as Endangered on the Red List of South African Plants.

Above: Babiana patersoniae

Babiana patersoniae

Babiana patersoniae is one of the more common Babiana to be found in Overberg Renosterveld. It is easily identified by the scent of the flowers, with the blooms smelling strongly of cloves. The scent becomes much stronger at night, indicating a possible moth pollinator. This species grows on clay slopes in Renosterveld vegetation from Caledon in the western Overberg eastwards to the Eastern Cape.

Above: Babiana patula variations

Babiana patula

This species is known from around twenty populations, distributed from Tulbagh to Albertinia where it grows on clay flats and lower slopes in Renosterveld vegetation. The flowers are mauve to blue in colour with yellow markings and are sweetly scented. Around 60% of the habitat of this species has been lost due to transformation for agriculture and urban development and population decrease is ongoing.

Above: Babiana purpurea

Babiana purpurea

Babiana purpurea is easily recognised by its spectacularly bright pink to purple flowers. It grows on clay flats and slopes in Renosterveld vegetation from Botrivier to Robertson and Bredasdorp.. It is listed as Endangered on the Red List of South African Plants and its stronghold is within the largest remnants of Western Rûens Shale Renosterveld, among our easement sites in this vegetation type.

Above: Babiana stricta

Babiana stricta

Found in clay soils in Renosterveld from Piketberg southwards to the Cape Peninsula and eastwards to Swellendam, Babiana stricta has a relatively wide distribution. It grows in waterlogged areas on gravelly soils in Renosterveld or Fynbos vegetation. Despite it’s relatively wide distribution, Babiana stricta has lost 47% of subpopulations as a result of habitat loss from transformation for agriculture and urban development. Habitat loss and population decrease for this species is ongoing with further threat presenting in some areas from habitat encroachment by alien grasses. It is therefore Near Threatened on the Red List of South African Plants.

The Renosterveld of South Africa’s Overberg encompasses some of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems. Sadly, they are also some of the most threatened, under siege from all sides from illegal ploughing, overgrazing, often inappropriate fire regimes, drift from agricultural chemicals and much more. This extraordinary vegetation once covered the Overberg’s wheat-belt, but following extensive transformation for agriculture, only around 5% of its former extent remains.

This Endangered Species Day we are going to take a closer look at the Aardvark, Aardwolf and Bat-Eared fox, three different insect-eating mammals that call Overberg Renosterveld home. They may not be considered highly threatened across their whole distribution range, but all three are steadily decreasing in number in the Overberg.

Aardvark (Orycterocarpus afer)

Aardvark (Orycterocarpus afer) are medium-sized nocturnal burrowing mammals that feed on ants and termites. They are found across the southern two thirds of the African continent. They have a long pig-like snout that is used for sniffing out food which they dig out with their powerful clawed front feet. They are listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List but are extremely rare in the Overberg.

The Aardwolf (Proteles cristata)

The Aardwolf (Proteles cristata) also has a wide distribution range, extending across southern and east Africa. They may look like ferocious predators ready to take down large prey, but in fact they are exclusively insectivorous, eating only insects and insect larvae with their long sticky tongues. They predominantly subsist on termites, with one Aardwolf able to consume as many as 250 000 termites in one night. While they are not recognised as threatened throughout their range, they are rare in the Overberg but we have caught them on camera several times with our trail cameras.

Bat-Eared Foxes (Octcyon megalotis)

Bat-Eared Foxes (Octcyon megalotis) also are found across southern and east Africa. The majority of their diet consists of insects, in particular termites, but they will also eat ants, beetles, crickets, grasshoppers, scorpions and occasionally small mammals and reptiles. The insects that Bat-Eared Foxes consume meet the majority of their water needs too. The species has seen many dips and peaks in the Overberg and these population changes are believed to be due to rabies and distemper outbreaks. However, the added impact of their now-fragmented habitats make it difficult for their populations to ‘bounce back’ as they may have done in the past.

So why are these Renosterveld mammals decreasing in number and why are they becoming increasingly scarce in Overberg Renosterveld? Habitat loss is one of the main drivers of population decrease for all three of these species. Renosterveld, once ploughed, gives way to a monoculture desert of crops that is completely lacking in the termite food on which Aardvark, Aardwolf and Bat-Eared Foxes depend.

This habitat loss also leads to fragmentation of the habitat which remains, often leaving long distances in the landscape between surviving areas of Renosterveld. Many of the Renosterveld patches which remain are relatively small, having survived the plough only because the land on which they are is too steep or rocky for agricultural machinery. This means the plant and insect life that cling onto life in these fragments are further imperilled by drift from agricultural chemicals.

It is likely that many termite mounds in the Renosterveld today have lost their termite inhabitants due to the impacts of agricultural chemicals and major reductions in grass cover (on which termites depend) due to overgrazing. This is likely to have severe ramifications for our insect-eating mammals further up the food chain who depend on the survival of termites and other insects in the landscape to survive. However, we know little about the full impacts of these influences on our Renosterveld termites, with more conservation-focused research needed to better understand the impacts on survival of the broader ecosystem.

This serves to highlight the importance of research and conservation action not only being focused on the ‘cute and cuddly’ flagship species. There is a global dearth of knowledge, researchers and research being undertaken on the state of the world’s insects, despite them being ecosystem lynchpins as pollinators and as food for other species further up the food chain. If the insects are lost our ecosystems will rapidly collapse.

Image above: Aardwolf scat

Furthermore, our Aardvark, Aardwolf and Bat-Eared foxes were sadly misunderstood and maligned creatures within the agricultural landscapes of the Overberg. Bat-Eared Foxes and Aardwolf were, in the past, often feared and unnecessarily persecuted by farmers because they believed them to be a threat to their livestock, when in fact they are harmless predators of termites and other insects. Luckily, awareness amongst farmers is changing and very few maintain such attitudes. Many of these beautiful and harmless mammals also lose their lives as roadkill, as increasingly roads bisect their territories that are increasingly providing reduced quantities of food.

This story most importantly tells us that we shouldn’t adopt a ‘one size fits all’ approach to conserving species and ecosystems and monitoring is key to ensure that locally applicable threats that may not apply across the entire range of a species are recognised and mitigated where possible. The data on the Red List may not always tell the whole story. All species form a key part of the ecosystems in which they live, and even though a species may be locally threatened in one area and common elsewhere, it doesn’t mean that it’s value and importance to be conserved as part of a functioning ecosystem is diminished elsewhere.

Image above: Aardwolf

So what can we do to conserve the Aardvark, Aardwolf and Bat-Eared Foxes of the Overberg? Firstly we need to conserve our Overberg Renosterveld habitats in perpetuity, so that further habitat loss doesn’t push these species further towards the brink of local extinction. To this end we encourage any landowners with Renosterveld on their land to consider joining the ORCT’s Conservation Easement Project.

Secondly watercourses on agricultural land act as vital corridors for these mammals and other species to move through the landscape between patches of Renosterveld vegetation. We therefore encourage farmers to leave appropriate buffer zones when ploughing between productive lands and watercourses. This also helps to decrease soil erosion and reduce pollution of watercourses. Also when driving on the roads of the Overberg, particularly at night, keep an eye out and spare a thought for wildlife crossing, and give them a right of way to safety.

We would like to thank the many farmers of the Overberg that work alongside us in conserving their Renosterveld. WWF South Africa, as well as Hans Hoheisen Charitable Trust, the Mapula Trust and the Ford Wildlife Foundation are also acknowledged for their support for the ORCT’s Conservation Easement Programme.

Please consider supporting the vital work of the Overberg Renosterveld Conservation Trust to help them manage and conserve more of our Renosterveld ecosystems and their wildlife in perpetuity.

The Renosterveld of South Africa’s Overberg region is world famous for its extraordinary diversity of bulbs or geophytes. One of the most well-known genera are the Gladiolus. Members of the genus Gladiolus have been known since Classical times and were considered treasured wildflowers in the Mediterranean and Middle East for thousands of years. The genus name Gladiolus in Latin means ‘little sword’, in reference to the shape of the leaves, a common trait in members of the Iridaceae or Iris family.

There are around 260 species of Gladiolus, coming from Europe, the Middle East, through tropical Africa to Namaqualand and southwards to the Cape. Overberg Renosterveld is home to a stunning and highly varied range of species from this well-known genus, and here we will take a look at a small selection. Some are common and widespread, others are known from just a handful of sites. All of the species discussed here have a fascinating range of floral adaptations to attract a range of specialist pollinators.

Gladiolus abbreviatus

This quirky looking customer looks very unlike other members of the genus and caused considerable confusion among plant taxonomists prior to its classification as part of the genus Gladiolus. Gladiolus abbreviatus grows on clay and shale banks in Overberg Renosterveld from immediately west of Caledon eastwards to Riversdale. It is most commonly found on south facing slopes which are wetter and more sheltered, as well as watercourses or drainage areas. In Afrikaans this plant is also known as Slangkop or Suikerkannetjie.

Flowering time is predominantly from June to August but blooms are sometimes found as late as September. They are adapted for pollination by sunbirds, with recorded visits from Malachite Sunbirds which are thought to be the main pollinator. Gladiolus abbreviatus often grows in association with other red flowered species also pollinated by sunbirds such as Lessertia frutescens and Watsonia aletroides.

Subpopulations of Gladiolus abbreviatus are highly fragmented and this species has experienced considerable habitat loss as a result of lowland habitat transformation for agriculture. Several of these surviving subpopulations are in small fragments of renosterveld in road reserves and drainage areas. Invasive alien plants further contribute to habitat loss for this species. It is therefore listed as Vulnerable on the Red List of South African Plants.

Gladiolus acuminatus

This sweet-scented beauty is endemic to the Overberg and is currently known from no more than five localities. It was first brought to the attention of botanists and described after being spotted by Rudolph Marloth at the Caledon Wildflower Show in 1916. To this day the collector or locality of the type specimen is not known. It wasn’t until 1932 that this species was recorded in the wild.

Today Gladiolus acuminatus is known to be distributed from Caledon to Bredasdorp where it grows on flats and north facing slopes in Renosterveld. It is a relatively poorly recorded species and known from just a few collections in the wild. Flowering time is from mid-August to late September. The sweet scent of the pale coloured blooms combined with the presence of long floral tubes suggests that Gladiolus acuminatus is moth pollinated, however, little is currently known about its pollination biology. More research is needed about this species. It is listed as Endangered on the Red List of South African Plants.

Gladiolus brevifolius

Gladiolus brevifolius is one of the most common autumn flowering Gladiolus from South Africa’s winter rainfall zone. It is also known as Autumn Pipes or March Pipes. This species is distributed from Piketberg southwards to the Cape Peninsula and eastwards to Montagu where it grows in association with a variety of different vegetation and soil types. It is relatively variable throughout its range. Flowering takes place predominantly during March and April but occasionally will occur as early as February.

Gladiolus lilliaceus

This spectacular Gladiolus is one of the largest to be found in the Renosterveld of the Overberg. It is also known as the Large Brown Afrikaaner, Aandpypie, Grootbruinafrikaaner, Kaneelaandblom or Ribbokblom in Afrikaans. Distributed from the Cederberg through to Port Elizabeth in the Eastern Cape, Gladiolus lilliaceus grows on clay soils in renosterveld vegetation.

Flowering takes place from August through to November. The tepals of the flowers are a rusty orange colour during the day but at sunset they change colour to a translucent mauve, releasing a strong scent of cloves. It is thought that this is to attract moth pollinators that become active at dusk.

Gladiolus patersoniae

Easily recognisable with its beautiful and delicate purple and white blooms, Gladiolus patersoniae was named after Eastern Cape naturalist Florence Paterson, who made the type collection of this species in the Baviaanskloof mountains in 1910.

This species has a relatively large distribution, being found from Worcester through to the Southern Cape mountains and eastwards to the Baviaanskloof mountains. Few other Gladiolus grow at such a high altitudinal range and across such high climatic variability. Flowering takes place from August to September at lower elevations and as late as October and November for higher altitude subpopulations. The flowers are pollinated by long tongued bees.

Gladiolus tristis

Perhaps one of the most well-known Gladiolus of Overberg Renosterveld, Gladiolus tristis is also known as the marsh Afrikaaner, Vlei-aandblom, Rheebokblom or Trompetters. Its species epithet ‘tristis’ means ‘sad’ in Latin, alluding to the relatively pale flower colours. Some even describe them as dull, but we don’t think so. The soft white/yellow blooms of this species are produced from August to November and occasionally December to January at higher altitudes. They were once popular as cut flowers but should not be picked, rather being left to be enjoyed in the veld, setting seed after flowering for the next generation of Gladiolus. The flowers only open completely in the late afternoon and evening and are sweetly scented. It is thought they are pollinated by Sphinx moths (Sphingidae).

Gladiolus tristis is a relatively widespread species, distributed from Nieuwoudtville on the Bokkeveld Escarpment southwards and east to Port Elizabeth in the Eastern Cape. It is particularly common in the Overberg from Bredasdorp eastwards to Riversdale where it can often be seen growing in dense colonies on damp flats. This species grows on both granite, shale and sandstone derived soils.

Gladiolus vandermerwei

The intense red blooms of this beautiful bulb look much like a tropical bird, with splashes of red visible in the renosterveld during spring where the highly threatened Gladiolus vandermerwei still survives. In fact, the flowers are pollinated by sunbirds.

It was named in honour of J.S. Van De Merwe who first collected this species in 1928. He gave plants that he collected to P. Ross Frames for cultivation and pressed specimens were lodged in the Bolus Herbarium (at the University of Cape Town). Gladiolus vandermerwei was described as a new species by Louisa Bolus in 1933 where it was initially placed in the genus Antholyza. It was later revised to genus Gladiolus in 1989 by Goldblatt and De Vos.

This species is distributed from Botrivier in the western Overberg eastwards to Heidelberg in the east of the region. It grows in Overberg Renosterveld on shale derived soils in dry areas, as well as on quartzitic outcrops in the eastern Overberg.

Gladiolus vandermerwei has lost more than 80% of its habitat owing to transformation for agriculture and is now only known from around ten highly fragmented subpopulations with fewer than 250 plants each. It is therefore ‘Endangered’ on the Red List of South African Plants.

Today we celebrate Valentine’s Day, the festival of romance and love celebrated worldwide. It is also known as Saint Valentine’s Day or the Feast of Saint Valentine, dating back to the 14th Century within the circles of English poet and author Geoffrey Chaucer.

The colour red is world-famous for being symbolic of this celebration, being associated with passion, romance, love and high status. Red roses have become a quintessential symbol of Valentine’s day. But who knew, right on our doorstep, that our local Overberg Renosterveld is home to many stunning red blooms of its own. In honour of Valentine’s Day we take a closer look.

A bloom of one of the most intense shades of red found within South Africa’s Cape Floristic Region, Brunsvigia orientalis is one of the first blooms of the year to emerge in Renosterveld, growing from the dry earth from February to March after the first rains of autumn.

They are distributed from Namaqualand southwards to the Cape Peninsula and eastwards to Plettenberg Bay on the Garden Route. Brunsvigia orientalis has a variety of common names, including the name ‘rolbossie’, so named because the dry flowerheads blow across the landscape in the wind, distributing the seeds far and wide.

This vygie is famous for its spectacular red blooms, which are pollinated by bees. These plants are referred to as ‘municipal workers’ as their flowers open in the morning at 9am and close by 5pm. A member of the Aizoaceae family, it is also known as the Worcester-Robertson vygie. Drosanthemum speciosum is distributed from Worcester to Barrydale where it grows on shale geology in Renosterveld, Fynbos and Karroid vegetation.

This species is one of the most spectacular succulents for use in the drier waterwise garden. They grow easily from both seed and cuttings, requiring moderate watering in summer and being kept dry during the summer months.

The spectacular red paintbrush-like flowers of Haemanthus coccineus emerge in the renosterveld from February to April. They are more commonly known as the ‘April Fool’. This species was most likely to be the first species to be collected from Table Mountain, seen illustrated in 1605 by the Flemish botanist de L’Obel.

Haemanthus coccineus occurs from southern Namibia down through the winter rainfall area of South Africa and eastwards as far as Makhanda (formerly known as Grahamstown) in the Eastern Cape.

The intense red blooms of this beautiful bulb look much like a tropical bird, with splashes of red visible in the renosterveld during spring where the highly threatened Gladiolus vandermerwei still survives. In fact, the flowers are pollinated by sunbirds. It was named in honour of J.S. Van De Merwe who first collected this species in 1928. He gave plants that he collected to P. Ross Frames for cultivation and pressed specimens were lodged in the Bolus Herbarium. Gladiolus vandermerwei was described as a new species by Louisa Bolus in 1933 where it was initially placed in the genus Antholyza. It was later revised to genus Gladiolus in 1989 by Goldblatt and De Vos.

This species is distributed from Botrivier in the western Overberg eastwards to Heidelberg in the east of the region. It grows in Overberg Renosterveld on shale derived soils in dry areas, as well as on quartzitic outcrops in the eastern Overberg.

Gladiolus vandermerwei has lost more than 80% of its habitat owing to transformation for agriculture and is now only known from around ten highly fragmented subpopulations with fewer than 250 plants each. It is therefore ‘Endangered’ on the Red List of South African Plants.

More commonly known as the Guernsey Lily, the species epithet of this beautiful bulb is named in reference to Sarnia, the Roman name for the English Channel island of Guernsey. Nerine sarniensis is however endemic to the Western Cape, found from Clanwilliam in the Cederberg southwards to the Cape Peninsula and eastwards to Caledon in the Overberg where it is found in both Fynbos and Renosterveld.

It flowers in profusion after fire and with diminishing frequency thereafter until the next veld fire moves through the landscape. Nerine sarniensis was introduced to Europe and first recorded in cultivation as early as 1634 in Paris and extensively cultivated on Guernsey by the late 1650s.