Black Harriers in the Overberg that have had satellite trackers placed on them are telling us an incredible story. We’re now able to see exactly where these birds move, and how far they travel. And we’re learning just how dependent they are on natural land – especially Renosterveld.

The Overberg Renosterveld Conservation Trust managed to tag three Black Harriers this year. Including the six birds trapped and tagged in 2021 (of which two died), we’re now monitoring the movements of seven birds in the Overberg.

ORCT Director Odette Curtis-Scott and her team joined world-renowned harrier expert Dr Rob Simmons (of the University of Cape Town) in tagging the birds. Odette and Rob started working on Black Harriers 22 years ago and the species became the focus of her Master’s degree. Now they are working together again and taking advantage of significant improvements in technology to deepen our understanding of these beautiful, charismatic birds.

Here’s what we’ve seen so far.

The satellite data has shown that while the birds are entirely dependent on natural remnants of Renosterveld for breeding, their foraging range covers a mix of transformed and natural habitats, where they mostly hunt Striped Mice and Common Quail.

- One of the males (simply named #88) breeding opposite the Excelsior windfarm, who has been wearing his GPS tag since 2021, has foraged within and beyond the Renosterveld, just south of the windfarm. As yet, he has not left his breeding grounds.

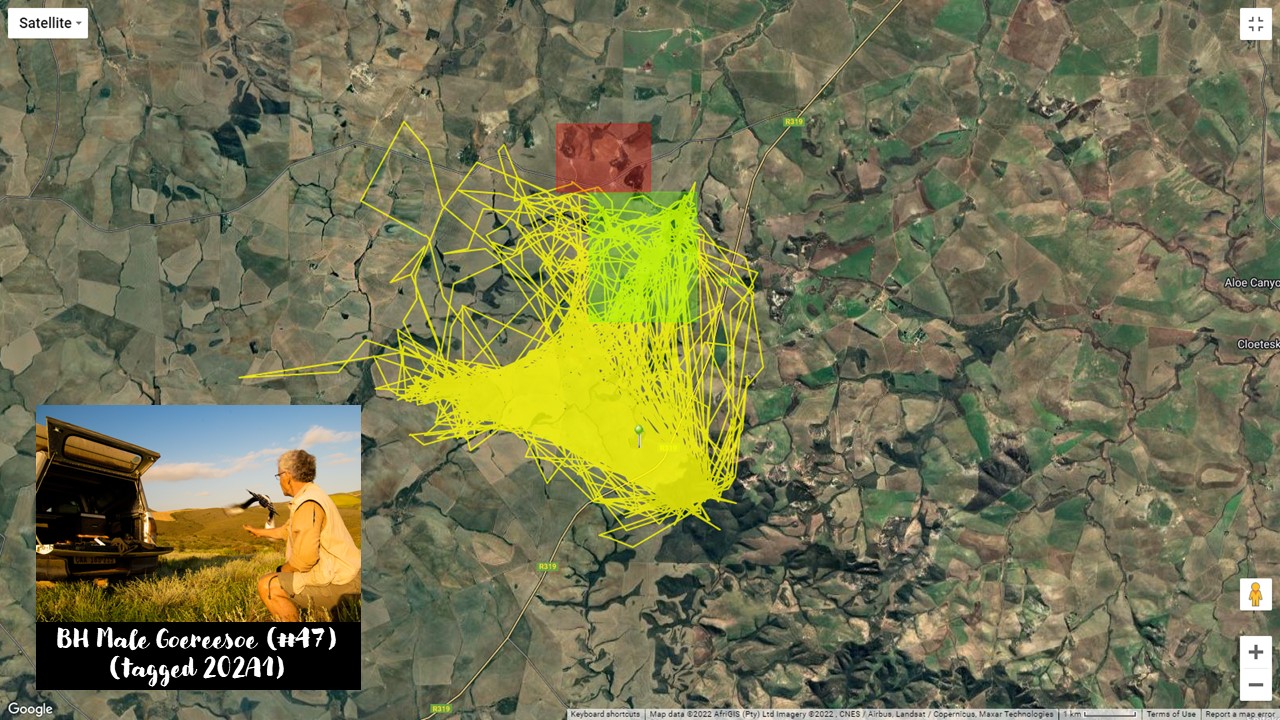

- However, male #47, also breeding opposite the windfarm, has been giving the team grey hairs, as he regularly forages within the windfarm, between the spinning blades. The monitoring team at Excelsior are doing their best to implement the shutdown on demand policy and keep him and all the other harriers and threatened birds that forage here safe. This adrenaline junkie has also not left his breeding grounds since he was tagged in 2020.

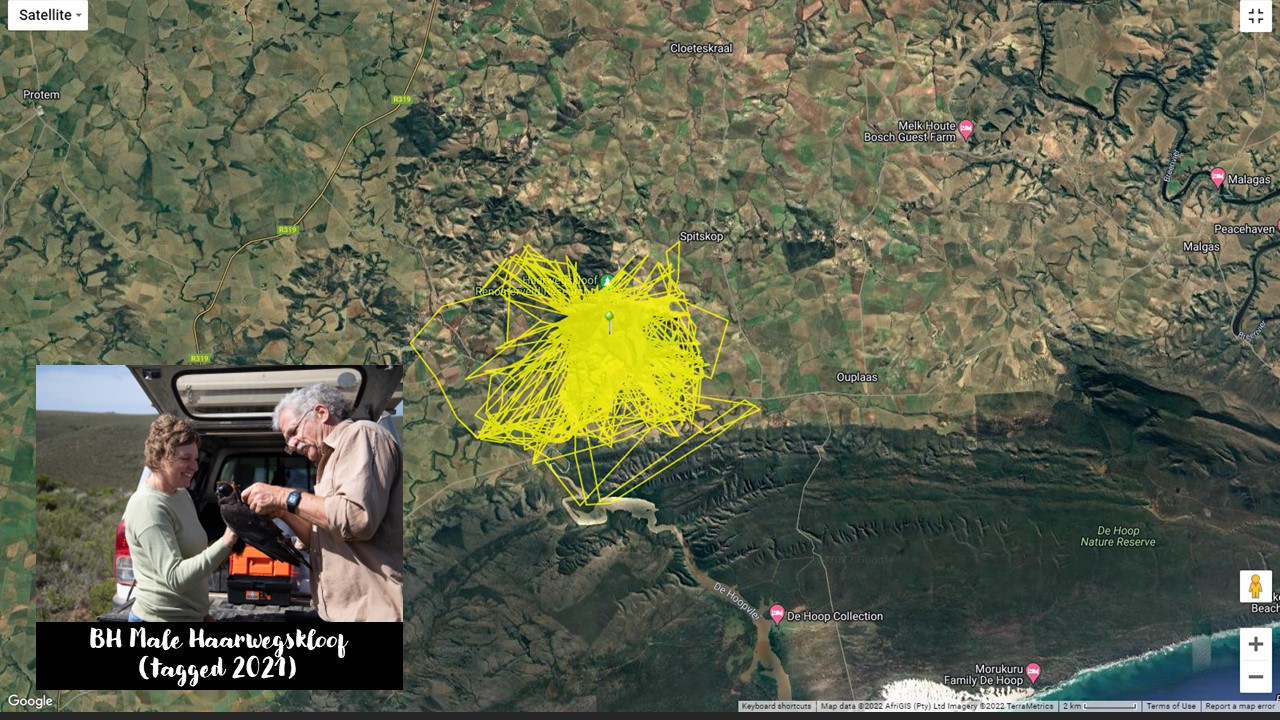

- Another male tagged last year at Haarwegskloof is also still on his breeding territory (and has raised two chicks this year). He makes use of the natural corridors and arable lands between the reserve and the De Hoop Nature Reserve. He has made only a few flights into De Hoop itself.

- Mesa, a female tagged this year, has raised three young chicks in a fragment of Renosterveld close to Haarwegskloof. She has used the patch – which is only around 4km² as her foraging grounds, with only a handful of trips beyond its borders.

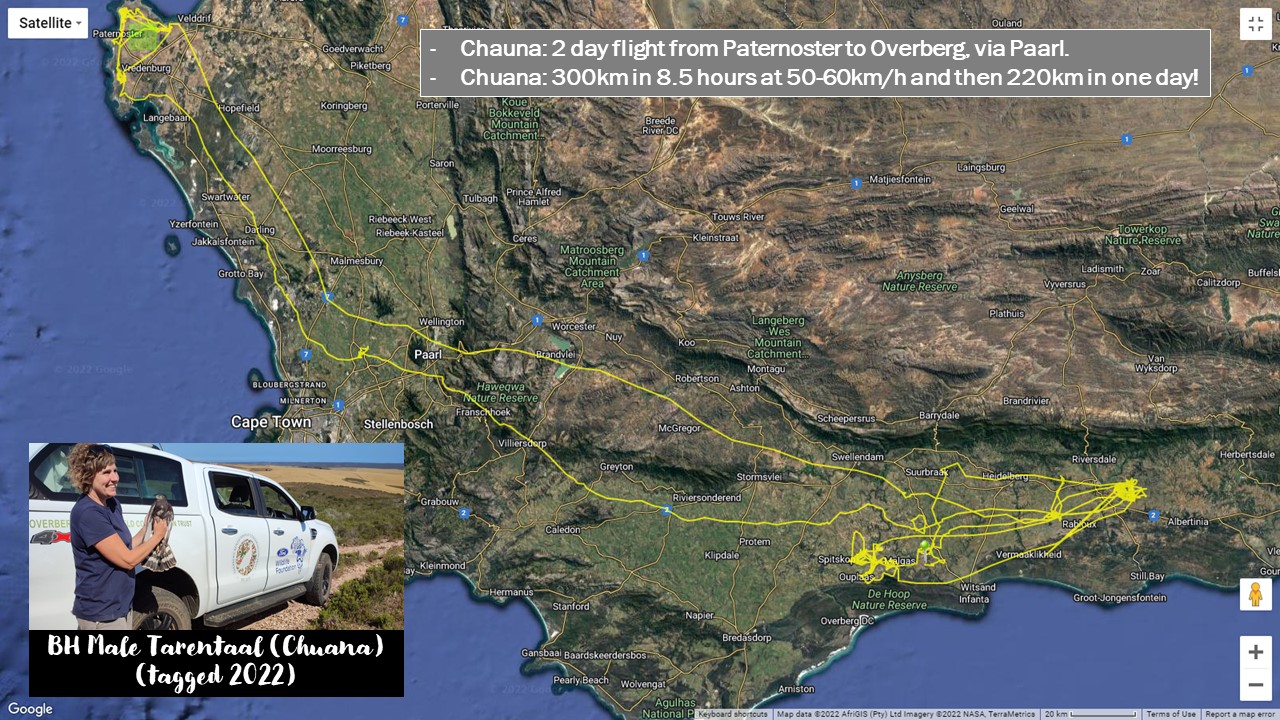

- Two individuals however spread their wings to get to know the Western Cape. Chuana, a male tagged this year, made an incredible two-day flight from Paternoster along the West Coast, via Paarl, to the Overberg. He flew 300km in 8.5 hours at between 50 and 60km/hour. He completed the final 220km the next day. He has also moved quite broadly across the Overberg and beyond, between Ouplaas and all the way up to lands just south of Riversdale.

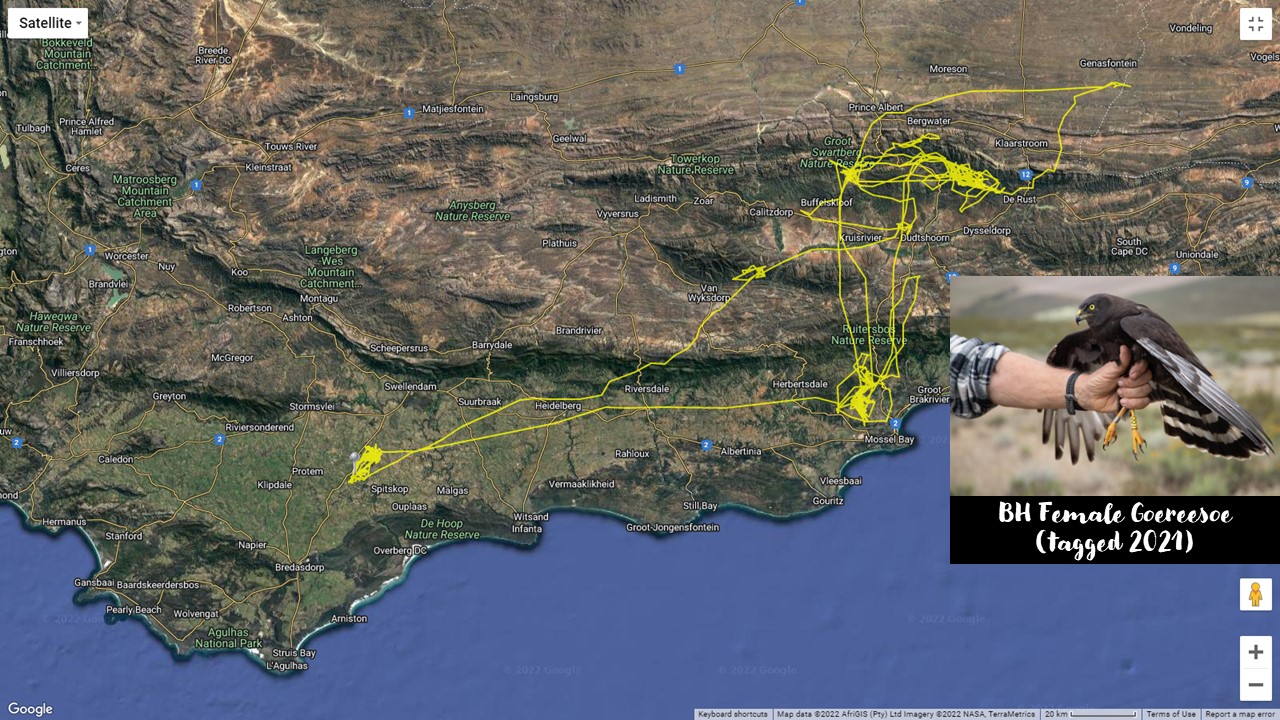

- Another female tagged close to the Excelsior windfarm in 2021 has undertaken long flights into the Groot Swartberg Nature Reserve north of Oudtshoorn and down to the Ruitersbos Nature Reserve north of Mossel Bay. She then returned to her breeding grounds and has been there ever since (although her tag has malfunctioned, so we will sadly not learn about her movements hereafter).

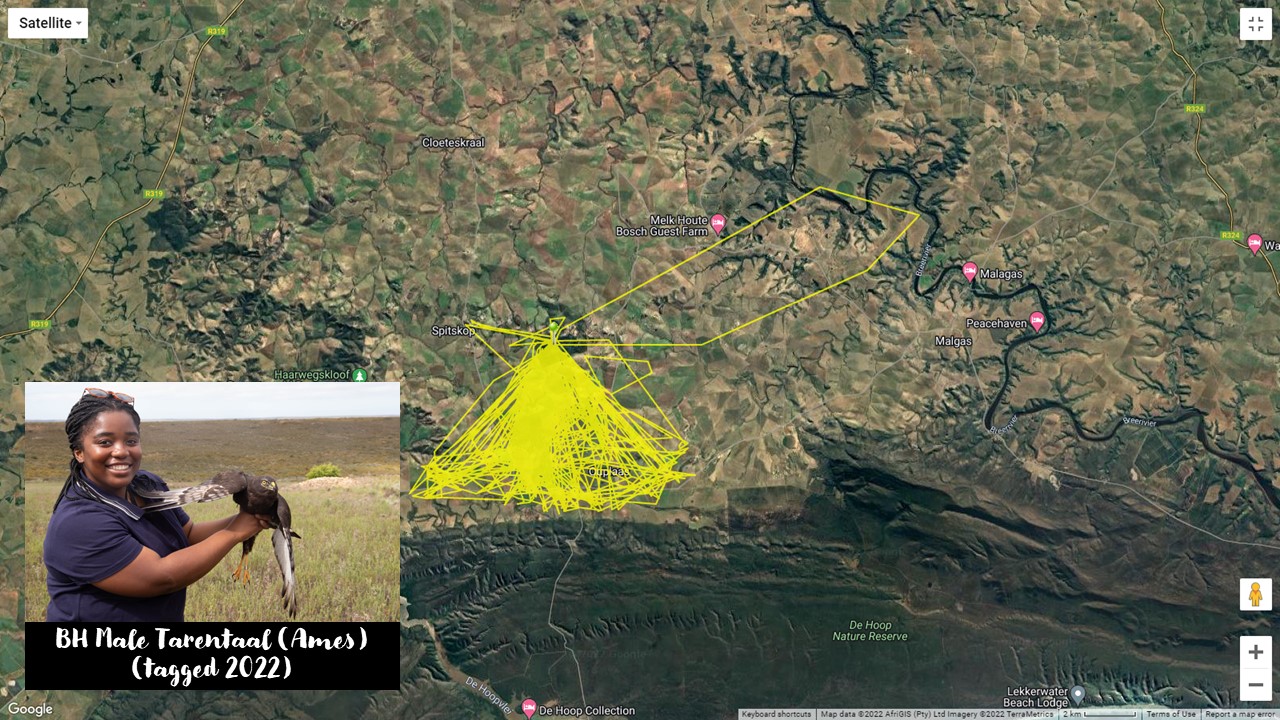

- Ames, a male tagged near Spitskop this year, also forages mostly over agricultural land surrounding the remnant of Renosterveld in which he is breeding.

Odette says, “We’ve already been able to get incredible datasets on the movement of these birds. It helps to form a picture of what landscapes they’re using. And also shows us where we must avoid threats like wind turbines.

“Most of the birds that have been tagged for the last one or two years have not left their breeding grounds, or when they did, they returned for the breeding season. We hypothesise that this is mostly due to exceptionally high numbers of their favourite prey, Striped Mice, over the last two years, due to the wonderfully high rainfall we received (after several years of drought). The harriers, therefore, had no reason to leave the area.”

She warns that following the dry winter experienced in 2022, this could change going forward. “We’ve seen some of the lowest rainfall ever recorded. Prey numbers are no doubt plummeting now and we expect that the harriers will move on from their breeding territories for the summer. The species can be nomadic, following good rains in search of prey, as can be seen on Rob’s blog of West Coast breeding harries. So monitoring the birds’ movement over the next few months will be interesting.”

Why are we doing this?

Because Black Harriers face enormous threats – and their very survival as a species is at stake. There are only around 1 300 adults remaining. And research shows that the population is falling 2.3% every year.

They’re highly prone to collisions with wind turbines – as was witnessed when an individual was killed at the Excelsior Wind Farm in November 2021. Given that the Overberg has been identified as a Renewable Energy Development Zone (in other words, a hotspot for renewable energy developments, particularly wind in this case), there’s additional reason for concern.

With their preferred breeding ground (Renosterveld) already lost by over 95% and continuing to be removed, the species will not be able to cope with this new threat of wind turbines. As a result, experts warn Black Harriers could be extinct in just 75 years.

An overwhelming response of our Black Harrier lovers

In order to understand how Black Harriers use the landscape so that we can mitigate threats, the ORCT ran a crowdfunding campaign on BackaBuddy. The goal was to raise funds for three new tags (which cost about R20k each). But thanks to the overwhelming response of our Black Harrier lovers, we were able to acquire nine new tags. The team hopes to fit the remainder of the tags next year as we add more monitoring information to what we already know.

According to Odette, the incredible support of the Renosterveld fraternity made this possible. “This time last year, we were all in tears. We had lost two tagged birds in the course of one day to unnatural, man-made causes.

“Now, a year later, we are better resourced to find answers which may assist us with dealing with the threats facing the species – thanks to the wonderful supporters via the crowdfunding campaign. And we are working with powerful partners like BirdLife South Africa to together try to bring about change.” In fact, the ORCT’s work with Black Harriers has been recognised by BirdLife South Africa, when we become a Black Harrier Species Guardian.

She says that Black Harriers still face enormous threats. “But we’ve made a start to try to protect this iconic Renosterveld species.”

Our donors:

We received donations from individuals, companies and organisations in our crowdfunding campaign, and we’re grateful to everyone. A special thank you to Cape Bird Club, Birding Africa, the Tygerberg Bird Club and the Dutch Montagu’s Harrier Foundation for each funding a tag. And to all our other individual donors – thank you. Here’s the list.

Click here to change this text