By Grant Forbes

They’re often overlooked and underappreciated. And these small black creatures are known to cause quite a bit of havoc in our homes and gardens.

Yes, we’re referring to animals from the Formicidae family, ants. Ants make up a staggering 15 to 20% of all terrestrial biomass! The only continent where you will not find them is in Antarctica.

Their higher classification, Hymenoptera, puts them with sawflies, bees, and wasps, to which they are closely related, given that they’re also able to sting. According to Antweb, there are nine subfamilies in South Africa, 71 genera and an estimated 628 species of which 218 are endemic. 204 of these species occur in the Western Cape, making it the second-most diverse province in the country after KwaZulu-Natal. What they lack in diversity they make up in sheer numbers.

Top: Simple hole in the ground the nest of this Anoplolepsis custodiens. Above left: Paper mache nest Crematogaster peringueyi. Above right: Nest build in the canopy of the shrubs

Ants are social creatures, always found in colonies.

If you see an ant, you can be sure there are more to follow. Pheromones play a very important role in communication between ants – often why you would see ants ‘touch’ one another when passing or allowing them to follow a trail. Ant colonies could look like a simple hole in the ground – but they lead to an extensive underground network of excavated tunnels, papery nests in the canopy of shrubs or trees, under rocks or in decaying plant material.

Ant families are governed by a queen and consist of numerous worker ants. Upon opening a nest, you would potentially see some eggs, larvae, pupae and a frenzy of worker ants running around, especially since you have disturbed them. Worker ants are almost exclusively female, typically categorised into two groups: minors and majors. Minors are tasked with the foraging for food and majors are larger and much more aggressive, defending the nest.

Other social systems or caste systems also exist within ants. Male ants, known as drones, share very little of the workload. They are short-lived, initially cared for in the nest until ready to leave the nest to find a female. After mating, not being able to care for itself, it dies.

Left: Orange sugar nest exposed under a rock showing workers, larvea, cacoons and drones (with wings). Right: Subfamily Myrmicinae workers with naked pupae.

Ants are incredible drivers of ecosystems, possibly keystone species and their fate is completely connected to the fate of healthy ecosystems – like Renosterveld.

They process tons of material daily and are the cleaners and recyclers. In other words, these tiny creatures keep these systems going, even potentially exceeding earthworms in their ability to turn the soil. Ants are major predators of other insects and are leading herbivores in processing plant material.

Above: Crematogaster peringueyi on Aspalathus burchelliana.

Top left: Camponotus niveosetosus on Lichtensteinia sp. flowers. Top right: Ants of the Myrmicinae subfamily carrying seed. Middle left, right and bottom: Camera trap images of some typical ant feeders in Renosterveld.

Above: Camponotus storatus (Blonde Balbyter) on Diosma fallax.

Above: Camponotus storatus (Blonde Balbyter) on Diosma fallax.

We are all familiar with the fact that some fynbos plants depend on ants for their survival and seed dispersal, better known as myrmecochory. This feature is still poorly understood in Renosterveld. Ants have established relationships with numerous other species. Common to us is the aphid/ant relationship that destroys our gardens. This can be seen on Aspalathus and other genera in Renosterveld. They also make up the diet of several creatures like Aardvark and even Honey Badgers.

Since last year we have been documenting some of the ants in Overberg Renosterveld.

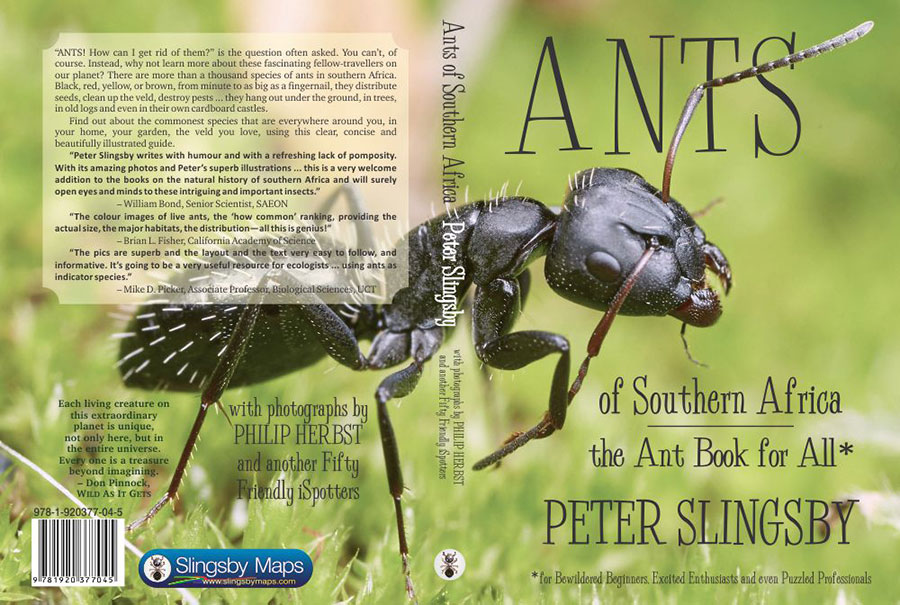

A friend of the Trust, Suretha Dorse, together with the field guide that we used to compiled this blogpost, Ants of Southern Africa by Peter Slingsby, infused us with a passion for these little creatures and created an interest to start studying them. Up to now we have been documenting the different species encountered sporadically when out busy with site assessments, surveys and natural resource management.